I recently taught one of my favorite workshop topics – how to build a plot points roadmap. I love talking plot and story structure, even though I know a lot of authors fear the plot as much as they fear the blank page. But for me, I don’t really know if a story is going to work until I see those major points articulated. As part of the discussion, I had a drawing up on the whiteboard behind me that showed the internal and external arcs and how action moves between them, and I promised to post a close-up of the arc after the workshop, so I decided to write a blog post articulating the process!

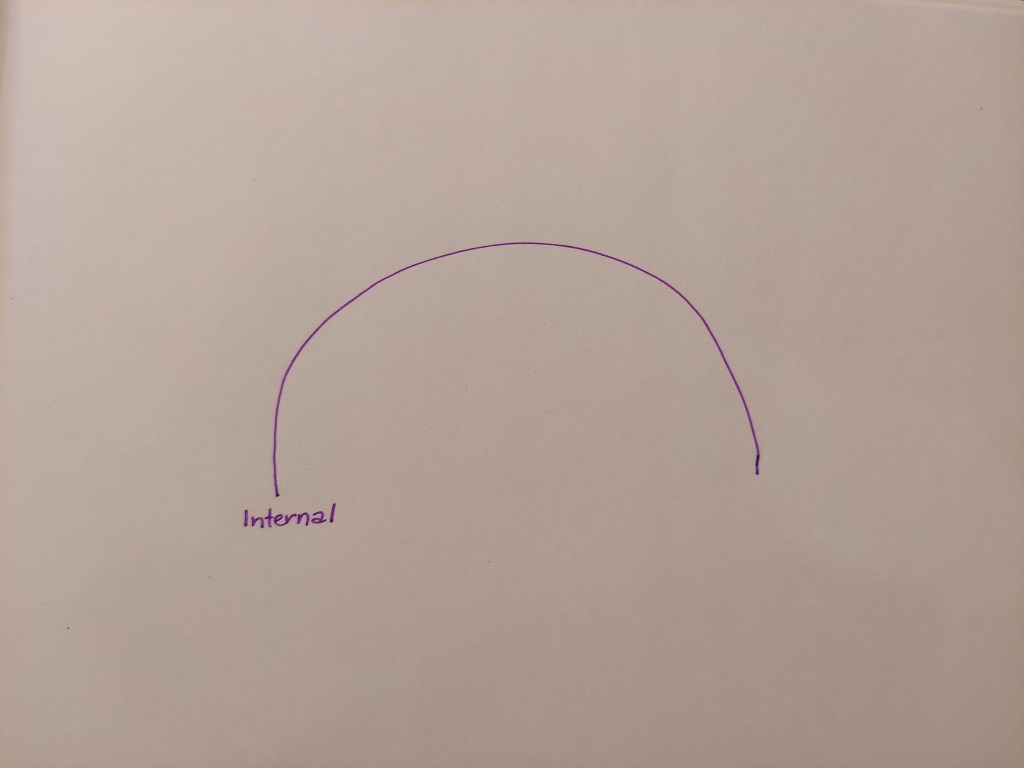

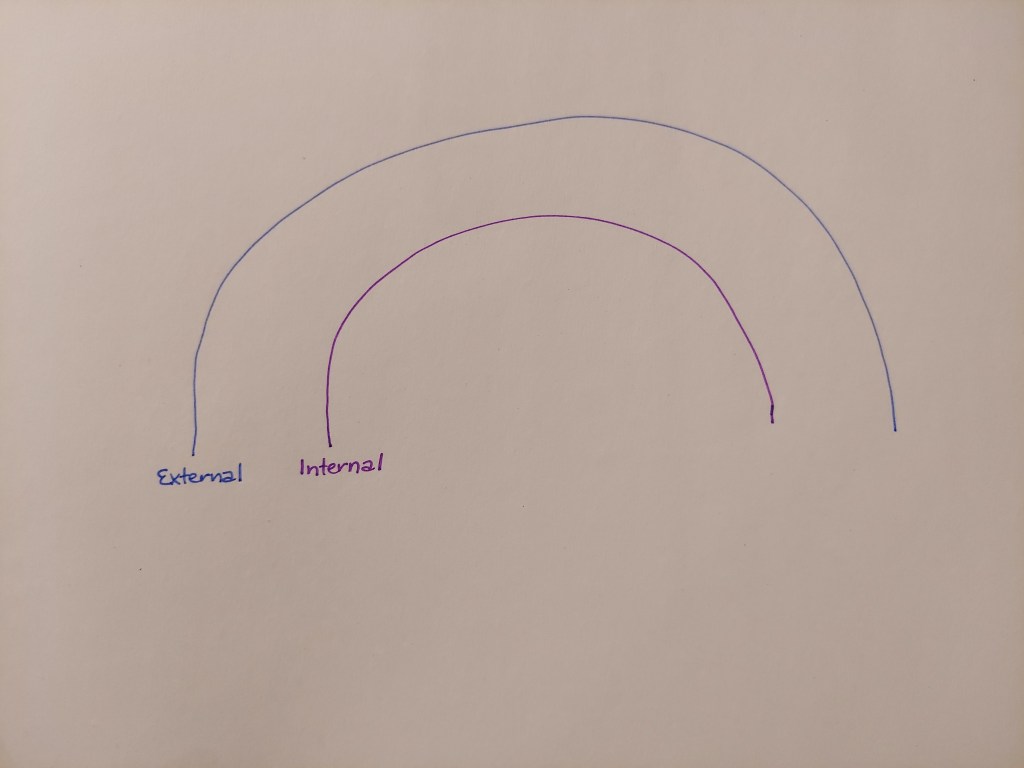

When it comes to story, there are generally two arcs happening at the same time: the internal and the external.

Internal is your character arc – their feelings, their wounds, the lies they believe about themselves and the world, the journey they’re on to becoming a better version of themselves. This is basically how your main character feels about what’s happening in the story.

The external arc is the physical action of the story, i.e. the plot (my favorite). It’s everything physical that happens to your character, and it’s the big outer arc that drives everything that happens internally. When you draw the arcs like this, it looks like a double rainbow. But the first thing you’ll notice about these arcs is what? They don’t touch. They look completely separate, which is what trips so many authors up when they’re first learning about plot. They think “oh, something random happens, and meanwhile my character is having all of these feelings, and then something else happens?? Idk”

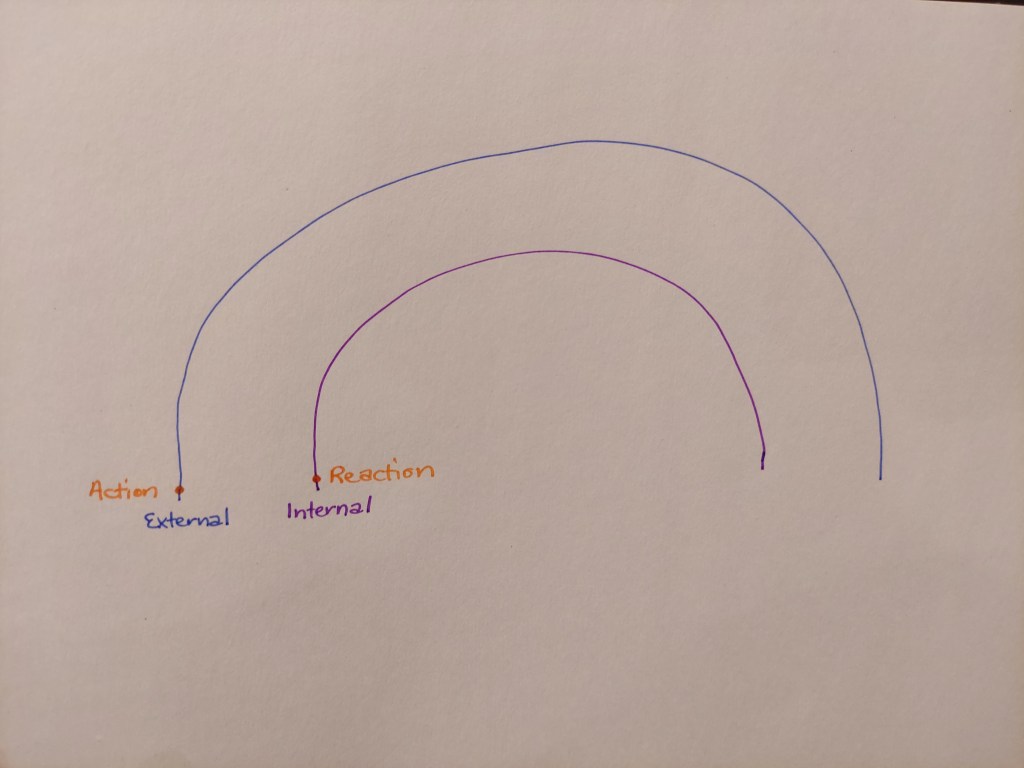

This is where the magic of the plot comes in. Because these two rainbows have a direct effect on each other in the form of ACTION and REACTION. Action is simply something that takes place in the external world. Your inciting incident is the first example of ACTION in your world – it’s always external, happens to the protagonist, and kicks off the story.

Now what? Well, plot and pacing are all about balance – action and reaction. So when an ACTION happens, your character needs to have a REACTION. Remember, the inciting incident is big enough that your main character can’t ignore it – it’s the knock at the door from a friend they haven’t seen in twenty years, or the mysterious letter in the post, or the dead body drop. So of course, when something that big happens, your character is going to have feelings about it. They might be surprised, or scared, or intrigued, or angry. That’s your reaction.

Whatever the reaction, it needs to be so strong that it drives your character to do something. Meaning, your character takes an ACTION. Maybe they slam the door in the old friend’s face, or they open the letter and learn they’ve been named in a will, or they hide the body. Whatever choice they make, it’s got to be rooted in that emotional reaction. But it creates an action out in the physical world.

Because your character has taken that physical action out in the world, there are consequences to that action. They slam the door in the old friend’s face, which causes the old friend to break a back window instead. They feel excited about the prospect of an inheritance so they answer the call to the will, only to find they have to share it with a long-lost twin sibling. And what happens after an ACTION? You guessed it, another REACTION.

The point here is that each action and reaction need to be big enough to drive the next point on the arc. If your action point isn’t big enough to get an emotional rise out of your character, it won’t properly drive the internal arc forward. And if your character isn’t reacting, then they’re not driving the story forward, either. All of these points are about creating propulsion, which makes for good pacing and plot. And eventually, if you’ve got your plot points roadmap all filled out and you’re using good action and reaction to drive the story between those plot points, you hit those magical two words: The End….on draft one, at least.

Leave a comment